In 1938, the U.S. Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against the eight major Hollywood studios: Columbia Pictures Corporation, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount Pictures, Inc., Radio-Keith-Orpheum, Twentieth Century-Fox Corporation, United Artists Corporation, Universal Corporation, Warner Brothers Pictures (“Paramount Decrees”). From the late-1920s with the advent of sound in motion pictures to 1948, when what would be known as United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. made the former distribution and exhibition practices of these studios illegal, the industry was functionally owned and operated by these select eight companies. The Paramount decision made it so that studios could no longer distribute films or own their own theaters without court approval; moreover, the Supreme Court struck down on block-booking, or “bundling multiple films into one theater license,” as well as various other price-regulation and film/building licensing practices (“Paramount Decrees”). This case affected not only the studios – bringing about an end to Hollywood’s studio system era, characterized by the monopoly studios had over the filmmaking process from casting to distribution – but how the American public would watch movies. It was now more affordable than ever for independent movie theaters to show studio films (meaning that more people in rural areas could now watch current films), and films made by independent studios could be shown to wider audiences. This, of course, was detrimental to the major studios, who still had actors, directors, producers, etc. under contracts – all legitimate reasons to want to stay in the movie business. Before the telltale signs of a failing business model would reveal themselves in the 1950s, the major studios put all of their energy into the marketing of their stars, primarily their established ones. A Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer contract player since 1942 and a star for longer, Katharine Hepburn would become one of the most bankable stars of the ‘40s and ‘50s and among the most recognizable of Hollywood’s classical period. And Hepburn, as a movie star, cannot be discussed without mention of her star persona: a modern woman, a progressive feminist.

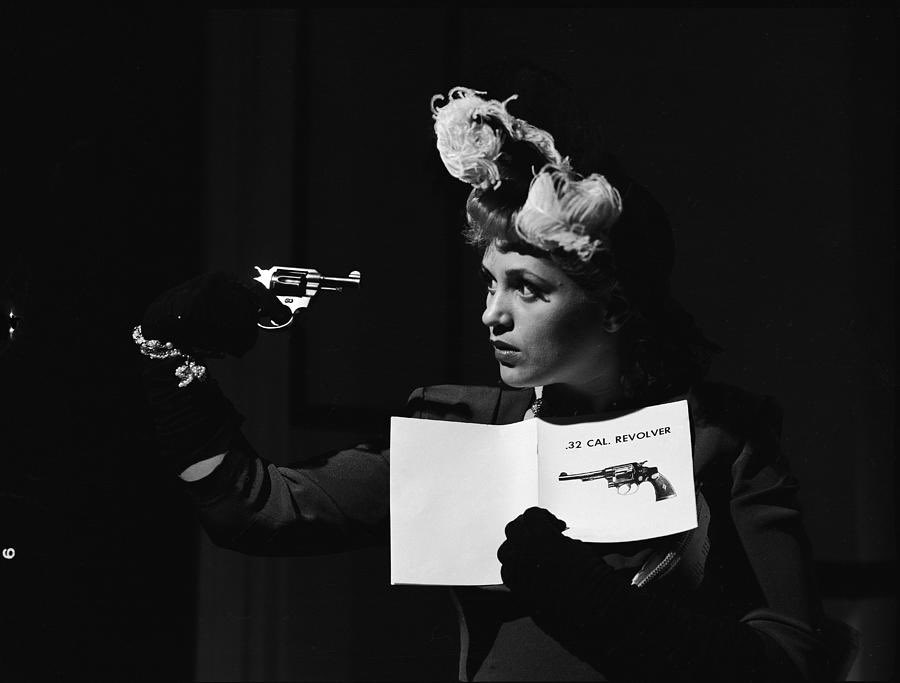

The antidiscrimination rhetoric of Adam’s Rib – released in November 1949 and starring Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy in the sixth of their nine films together – is not obscured by the conditions under which it was made; the fact that it was made at all, and imbued with such subversive themes, is indicative of its rhetors aims of challenging sexist norms. One of the stated conditions was known formally as the Motion Picture Production Code, in itself grounded in a deep cultural fear of media influence and disruption of the dominant heteropatriarchal order. In 1915, the Supreme Court ruled against free speech protection for motion pictures due to their unprecedented “capacity for evil,” and in 1930 the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) embraced the Code, or a set of rules under which all films had to abide (Kiriakou). The Code cast explicit restrictions on depictions of sex, crime, religion, race, and drug use, but between 1930 and early-1934, the Code was not as strictly enforced as it would come to be under the Production Code Administration (PCA). Beginning in July 1934, in the words of author Olympia Kiriakou, the PCA was “tasked with Code enforcement with staunch Catholic, Joseph Breen, at the helm. From that point onward until the Code was replaced with the ratings system in November 1968, no film could be shown in U.S. theaters without a PCA seal – save for a handful of exceptions” (Kiriakou). Just as Adam’s Rib was released in under the Code and in the shadow of the Paramount decision, the film was also released to an American public entrenched in Cold War anti-communist rhetoric, or the Red Scare. It was during this era that the House Un-American Activities Committee, first dispatched by the House of Representatives in 1938 to investigate alleged communist influences in American industry, was at the height of its legal and cultural powers. In fact, a member of the Adam’s Rib supporting cast, Judy Holliday (who plays defendant Doris Attinger), as well as its co-writer Garson Kanin, were both cited in Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television (1950) and were called to give testimony to the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) shortly thereafter (Barranger 13). Consumed in isolation, the politics of Adam’s Rib do not reveal themselves to particularly subversive, especially to the modern viewer; thus, Adam’s Rib as an antidiscrimination text must be considered within the context of its historical moment, in which such rhetoric was actively being suppressed by both the motion picture industry and the American government. Adam’s Rib, then, tells the story of a married couple – defense attorney Amanda and prosecuting lawyer Adam – battling it out in court, on opposite sides of a criminal lawsuit: Amanda defending Doris Attinger (on trial for shooting her unfaithful husband) and Adam representing Warren Attinger (Tom Ewell), the husband. Though the antidiscrimination rhetoric of Adam’s Rib cannot be satisfactorily communicated, this is not for a lack of feminist intention, due instead to the dominant conservative culture of its historical moment and the oversight of the Motion Picture Production Code; Adam’s Rib employs the conventions of the “woman’s film” genre to examine the discriminatory elements of the law and how they reinforce social barriers for women in both the workplace and domestic sphere, engaging film as a powerful tool in public discourse and effecting change in the cultural and legal stereotyping of women.

The framing of women in Adam’s Rib posits that sex discrimination is primarily, pervasively enforced through stereotyping. Conceptions of what women can or cannot do in order to be accepted by the hegemonic (white, heterosexual, capitalist) American society are peppered throughout the film, informing Amanda’s primary line of defense. A conversation between Amanda and her secretary, Grace, early in the film reveals the beginnings of her character reconciling how gendered difference directly informs courts of law: to her question, “What do you think of a man who’s unfaithful to his wife?” Grace answers, “Not nice but…”; to the same question, but with the roles reversed, Grace offers, “Something terrible.” Amanda then questions why there is a perceived difference at all. “I don’t make the rules,” says Grace. “Sure you do, we all do” (Adam’s Rib 00:12:20-00:12:38). In this, Amanda makes the connection between law and culture that her counterpart, Adam, never makes in the duration of the film: Amanda interprets the law through a wider historical, moral lens, while Adam applies a strictly textualist interpretation. The difference between the lawyers’ approaches to their practices is intentional; underscoring their sex difference works doubly to satisfy its “battle of the sexes” romantic-comedy genre conventions and to comment on the ways in which antidiscrimination cases are created (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer). The fictional Attinger v. Attinger case parallels that of Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), a landmark case for LGBTQ+ protection under the law but a failure as an antidiscrimination case; the textualist approach to the case, interpreting sex (a class protected under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964) as applicable to sexual orientation, diminishes a storied history of discrimination against the entire LGBTQ+ community. As Adam’s textualist approach fails to win the case, Amanda’s approach – acknowledging stereotyping as a form of de facto (practices that exist regardless of legal recognition) discrimination – is valorized; though not a precedent-setting case in life like Bostock v. Clayton County, the film is convincing in its reflection of true-to-life legal approaches, which makes the final “not guilty” decision for Doris all the more resonant. To this point, the Attinger v. Attinger case fits into a dialogue with like sex discrimination cases; the defeminizing rhetoric that is applied to Doris by both Warren and Adam in his prosecution resembles that of the stereotypes levelled at Ann Hopkins of Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989). During Warren’s cross-examination, he repeatedly calls Doris “fat” and that because of this, he had stopped loving her for “at least three years” (Adam’s Rib 00:51:24-00:51:33). Similarly, after her testimony, Adam condemns Doris’ crying due to her “shrewishness,” calling her an “unstable and irresponsible mother” (Adam’s Rib 00:56:05-00:57:00). In Price Waterhouse, Hopkins was denied the position of a partnership at her accounting firm due to sex stereotypes that were posited as personality defects; as author Andrea Giampetro-Meyer writes in “Standing in the Gap: A Profile of Employment Discrimination Plaintiffs,” that because senior partners described Hopkins as “aggressive,” “abrasive,” and “macho,” the facts of the case “raised questions about whether Ann met the norms for her gender whether she was feminine enough” (Giampetro-Meyer 433). In Price Waterhouse and Adam’s Rib alike, sex stereotyping is characterized as the deprivation of equal opportunity and protection due to monolithic qualities that are individually inapplicable and ignorant to nuance; these stereotypes can disproportionately weigh against the offended individual and, as Amanda repeatedly points out, these would not be factors of consideration at all if the subject were a member of the opposite sex (Adam’s Rib 00:09:17-00:09:46).

As Amanda and Adam apply different interpretive lenses to the Attinger v. Attinger case, the primary form of tension (framed as comedy) between the two is their inability to understand the rhetoric of one another’s arguments; both parties remain in different levels of stasis. Considering stasis theory, an interventional tool that “provides analytical resources as critics work to identify the ‘position on which the controversy depends,’” Amanda is stuck on the issue of quality (considering the justification/motivation for Doris’ action) while Adam is preoccupied with the issue of policy (deciding how, based on Doris’ action and her action alone, how the case should proceed) (Kornfield 257). In her book Framing Female Lawyers, author Cynthia Lucia writes that for Adam’s Rib, “the very crime at the center of the story–a woman’s attempt to murder her unfaithful husband–provides the nucleus around which [legal (workplace) and cultural (domestic)] issues revolve” (Lucia 29). This is to say that because Amanda is interpreting Doris shooting her husband in the context of domestic abuse against her (Warren having admitted to beating Doris on multiple occasions), and within the larger cultural context of women being ostracized for acting out of self-defense while men who do the same thing are exonerated, she is considering Doris’ motivations as legitimate means to bring antidiscrimination rhetoric into the case (Adam’s Rib 00:50:46-00:51:33). As Marianne Constable writes in “On Not Leaving Law to the Lawyers”: “Language implies, evokes, reveals, contradicts, inspires, and more”; Amanda is applying this very legal/cultural synthesis to Doris’ case, which she sees as much more than self-defense: the makings of an antidiscrimination case (Constable 81). Meanwhile, because Adam is a textualist thinker – arguing that if a law is bad “then the thing to do is to change it, not just to bust it wide open” – he is fixated on coloring Doris as an unstable person and trying her for attempted murder under the basic facts of the case, and nothing more (Adam’s Rib 1:10:21-01:10:42). What Adam is fearful of but cannot articulate is “slippage,” or “the inconsistencies between the production of legal meaning and its cultural reception” (Sarat and Simon 54). As he asks a pro-self-defense Amanda before the trial starts, “What do you wanna do, give her another shot at him?”, that Adam is only concerned with how a broad interpretation of the law can lead to precarious cultural impact, this gives us a key insight into why he just cannot see Amanda’s antidiscrimination rhetoric with a level eye (Adam’s Rib 00:09:17-00:10:01). Because both are addressing two different issues, applying two different interpretations of the case and, in effect, the law, this disagreement translates into their domestic life – for this legal debate is a cultural one, after all. “In Adam’s Rib the institution of marriage fuels the difference debate,” writes Lucia, defining the cultural dimension of the film as a microcosm of American society: spaces where the woman is expected to be submissive to the man (Lucia 30). That the domestic lives of Amanda and Adam mirror their courtroom battle sends the message that though Amanda is “winning” in the workplace, she is actively failing in the home, and thus, is a disruption to the heteropatriarchal order. While Hepburn’s Amanda ultimately concedes to Tracy’s Adam at the bottom of the film, that his interpretation of the case was the “correct” one, in order to restore order in their relationship (and by extension, the home), the precedent is still there: Amanda wins the case, as an antidiscrimination case.

It is through the “woman’s film” genre that Adam’s Rib is able to discourse the inventive powers of law and culture in mid-century America; moreover, the historical moment of the film’s release was informed by Katharine Hepburn who, through her star persona, was implicated as a lens through which to view the politics of the film: inherently feminist, and in the case of Adam’s Rib in particular, antidiscriminatory. While the woman’s film generally refers to any film about, made by or for women, the woman’s film of the classical Hollywood period can be narrowed to “a subtype of the film [. . .] whose plot is organized around the perspective of a female character and which addresses a female spectator through thematic concerns socially and culturally coded as ‘feminine’” (“Woman’s Pictures”). Considering Hepburn as a primary rhetor in Adam’s Rib, a press release from the top of 1949 announces: “At the request of Katharine Hepburn, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer has purchased ‘Man and Wife,’ a screen comedy by Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon, as a prospective vehicle for her and Spencer Tracy” (Brady). The power of stars in this dubious era of the classical Hollywood era to initiate the filmmaking process was incomparable to that of studio brass. That, as this press release reveals, Hepburn’s star power was so significant as to warrant her studio’s (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer) purchase of a script (Garson Kanin’s “Man and Wife,” an early title for what would later become Adam’s Rib) for the purpose of their appearance in the film adaptation, speaks to the recognition and resonance of her own distinctly feminist star persona among the moviegoing public (and American culture at large). Further, author Thomas F. Brady suggests that in the acquisition of this script, Hepburn would indeed be infusing her persona into the female attorney she would be playing in Adam’s Rib. In the film’s promotional materials, the genre of Adam’s Rib is made explicit through written and visual language. An advertisement published in the December 1949 issue of Modern Screen fan magazine depicts Hepburn and Tracy in a tug-of-war over a pair of pants; Hepburn’s face reads as determined, while Tracy’s face reveals a man disgusted – the trademark Hepburn-Tracy dynamic. The film’s tagline is positioned between the warring pair, reading: “MGM hands you the biggest laugh in 10 years! It’s the hilarious answer to who wears the pants!” (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer). The use of this clichéd phrase “who wears the pants” works to promote how, through the romantic-comedy genre, the film interrogates the issue of sex, making explicit its central conflict and the discourse surrounding. Context clues about Hepburn’s star persona indicate to readers of the fan magazine – and viewers of this wide-release advertisement, the moviegoing public – that her character will argue for women’s rights, and stand a good chance at beating out her competition in Tracy. In marketing a sex-based platitude and the star persona of Hepburn, this advertisement plays up to the antidiscrimination rhetoric of the film in order to attend to a female-centric audience. As fan magazines, which “democratized” the accessibility (or, constructed the public perception) of the motion picture industry and the stars in its makeup, modern scholarship surrounding Adam’s Rib tends to construct the rhetoric of the film not entirely through the text of the film itself, but through its historical context, genre, and its principal rhetors (Hepburn, Cukor, Gordon and Kanin). In Elyce Rae Helford’s 2020 book What Price Hollywood?: Gender and Sex in the Films of George Cukor, the author analyzes Adam’s Rib through the lens of the Hepburn-Cukor partnership, which was based on like, progressive ideals; as Helford puts it, “director and actor worked together with the restrictive framework of the romantic-comedy genre to revive Hepburn’s image with the movie-going public, from alienation to applause” (Helford 34). The throughline in all of Hepburn’s classical-era collaborations with Cukor – A Bill of Divorcement (1932), Little Women (1933), Sylvia Scarlett (1935), Holiday (1938), The Philadelphia Story (1940), Keeper of the Flame (1942), Adam’s Rib (1949), Pat and Mike (1952) – is Hepburn’s portrayals of women as close to her own (publicity-trained) personality: honest, independent, and mostly unyielding. In her pairing-within-a-pairing, Tracy as her counterpart in a Cukor film, the element of gender becomes aggrandized as performance; Tracy is hyper-masculine and because Hepburn is not hyper-feminine in a time where this was expected of a female star, her expression as a relative non-conforming woman becomes the primary source of the film’s tension (comedy). Such is the case with Adam’s Rib, as Helford observes: “The courtroom and the Bonner bedroom become stages, each with its own audience: fellow counsel, judge, and jury in the former and spouse in the latter” (Helford 44). Though by the end of Adam’s Rib, as in her other Tracy pairings such as Woman of the Year (1942), where the pressure to conform to sex stereotypes is made evident through Tracy’s internalization of heteropatriarchal order (his characters often representing the ideals of the Code), Amanda submits to Adam’s “superior” legal opinion (and thus, resumes her place as wife), her submission only comes out of desperation; when Adam threatens to shoot himself, she inadvertently subscribes to his logic that no person should be threatening others/their own lives with a gun, which wins him over but, at the same time, it is revealed that the “gun” was actually made of licorice. This comedic framework is significant in that it does not entirely position Amanda as a subordinate, rather a staunch advocate of her own beliefs, worn down only by a brief moment of panic in which anybody in her position would do the same to save the life of a loved one. Adam’s Rib, then, not only stands as a film about sex, but as a film in which the primary action, moral and emotional core is driven by the woman. It is Amanda who brings to court a bevy of female witnesses in support of her claim that “woman as the equal of man is entitled to equality before the law”; it is Amanda who earns Doris her “not guilty” verdict; it is Amanda who turns a self-defense case into an antidiscrimination case; it is Amanda, as Hepburn, who imbues the film with feminist intention (Adam’s Rib 1:02:10-01:02:44).

About ten minutes into Adam’s Rib (1949), Amanda and Adam debate the legal and moral implications of a Doris shooting her adulterous husband: “Now look, all I’m trying to say is there are lots of things that a man can do and in society’s eyes it’s all hunky-dory. A woman does the same thing, the same mind you, and she’s an outcast.” To Amanda’s observation, Adam asks if she’s finished; “No. Now I’m not blaming you personally Adam because this is so [. . .] All I’m saying is why let this deplorable system seep into our courts of law where women are supposed to equal,” Amanda continues. “Mostly I think females get advantages,” retorts Adam. “We don’t want advantages, and we don’t want prejudices” (Adam’s Rib 00:09:17-00:09:46). Adam’s Rib attempts to communicate how social barriers for women are reinforced through law and how the law creates social barriers for women, that sex discrimination is not just institutional but culturally pervasive through stereotyping, and, perhaps most directly: antidiscrimination law can be invented through antidiscrimination rhetoric. Considering Adam’s Rib as an antidiscrimination text, then, expands the canon of antidiscrimination texts, creating more cultural context and legal precedent to draw from in future antidiscrimination inventions. Moreover, that this rhetoric is achieved through film, the woman’s film of the classical Hollywood period in particular, credits film as a legitimate and effective means of impacting cultural and legal discourse. Ann MacGregor writes of Katharine Hepburn in a 1950 profile on the actress for Photoplay magazine, promoting the release of Adam’s Rib: “She wants others to have the freedom she demands, too, therefore, when speaking or working for what she believes, she doesn’t weigh consequences” (MacGregor 77). While about Hepburn, this line may well be describing Amanda Bonner, the politics of Adam’s Rib, the aims of the woman’s film, and antidiscrimination law, too.

Works Cited

Adam’s Rib. Directed by George Cukor, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1949.

Barranger, Milly S. “Broadway’s Women on Trial: The McCarthy Years.” Journal of American Drama and Theatre, 2003, pp. 1-37.

Brady, Thomas F. “Metro Buys Story for Miss Hepburn.” New York Times, 31 January 1949.

Constable, Marianne. “On Not Leaving Law to the Lawyers.” Law in the Liberal Arts, Cornell University Press, 2005, pp. 69-83.

Giampetro-Meyer, Andrea. “Standing in the Gap: A Profile of Employment Discrimination Plaintiffs.” Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law, 2006, pp. 431-41.

Helford, Elyce Rae. “Collaboration and Chastisement: Cukor Directs Hepburn.” What Price Hollywood?: Gender and Sex in the Films of George Cukor, University Press of Kentucky, 2020, pp. 34-48.

Kiriakou, Olympia. “A Fine (Hitchcockian) Romance: Sex, marriage, and censorship in Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1941).” The Screwball Girl, 16 November 2022, https://thescrewballgirl.com/2022/11/16/a-fine-hitchcockian-romance-sex-marriage-and-censorship-in-mr-and-mrs-smith-1941/.

Kornfield, Sarah. “Fixating on the Stasis of Fact: Debating ‘Having It All’ in U.S. Media.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 2017, pp. 253-289.

Lucia, Cynthia A. Barto. “The Law Is the Law: Adam’s Rib and The Verdict.” Framing Female Lawyers: Women on Trial in Film, University of Texas Press, 2005, pp. 27-45.

MacGregor, Ann. “Katie’s Hep!”. Photoplay, April 1950.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer advertisement. Modern Screen, December 1949, p. 3.

“The Paramount Decrees.” The United States Department of Justice, 7 August 2020, https://www.justice.gov/atr/paramount-decree-review.

Sarat, Austin, and Jonathan Simon, eds. Cultural Analysis, Cultural Studies, and the Law: Moving Beyond Legal Realism, Duke University Press, 2003.

“Woman’s Pictures.” Encyclopedia.com, 29 November 2022, https://www.encyclopedia.com/arts/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/womans-pictures.